Chasing S-Curves: Math and Personal Growth

Getting Better Gets Harder #

Narratives are really important to me, and I’m always looking for analogies between different experiences in my life. I just started at a new client this week, and had a very interesting conversation about staff turnover. The team described an encroaching feeling of stagnation accompanied by all the “good” people leaving. The client didn’t have any direct action plans about what to do, either – there was a lot of nostalgia for the “good old days” of two years ago,when everyone was excited and engaged. One member seemed confused by how they could have been so excited about the transition to Clojure and implementing agile practices, and how, now that the transition has been accomplished, so many good people are leaving.

There’s obviously a potential blog post here about building a strong engineering culture and sustaining a high-performing team, which I plan to write eventually. Today, though, I also found myself tying this conversation into personal development. The situation seemed directly analogous to a conversation that many in my friend group have been having a lot lately – how to sustain growth and energy into the middle part of your career. I know a lot of ambitious, fast-moving people who have done an incredible job of climbing the ladder in their careers and their personal lives, moving from success to success. Everyone, though, eventually hits a point where they feel like they’re not moving forward anymore or the growth curve has plateaued, leaving them with a perception of stagnating.

What do I mean by stagnation? These are really successful folks by any fixed measure; what has changed is the rate of growth. For the purposes of doing some geeky math stuff, I’m going to use “awesomeness” as a generic metric. What’s the definition of awesomeness? Whatever you want it to mean! I’m purposefully keeping it vague, because to my mind, overly defining it misses the point. Awesomeness is hard to quantify, but we can posit some attributes that this metric has:

- a person or organization can be awesome at a particular skill (that team is awesome at quality control, that person is awesome at tennis);

- a person can be awesome in general, in a way that is related to but is more than just the sum of all of their skills;

- an organization can similarly be awesome in general, in a way that is related to but is more than just the sum of all of their people.

Awesomeness is hard to quantify in absolute terms, but it can be useful for relative comparisons – something can get more awesome over time, and one thing can be more awesome than another.

Graphing Awesomeness #

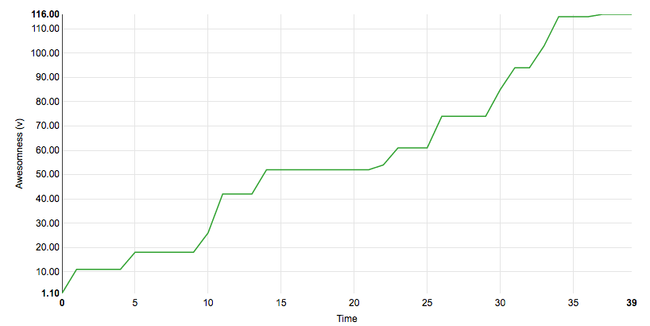

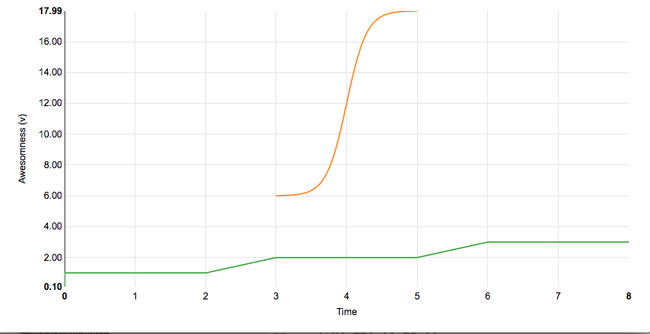

With that being said, I realized, like most people do, that personal awesomeness is almost never a straight linear function. Everyone has times that they feel like they are stagnant, and times when they feel on top of the world. I am a great believer in the idea that the grand arc of most people’s personal lives is one of ever-increasing overall awesomeness, but that progress generally looks something more like this:

None of this is new, right? Life goes in cycles, sometimes things are firing on all cylinders, and sometimes they aren’t.

What was interesting and insightful for me to think about was how this could be explained. This growth model could basically be modeled mathematically as being driven by “S-curves” – periods of exponential growth followed by a leveling off until the next period of exponential growth.

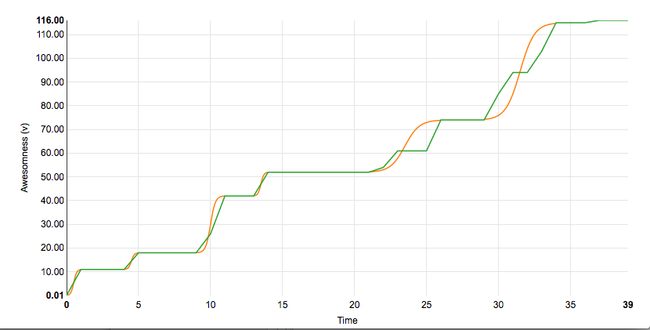

Let’s take a simple example: college! Your college education is a time of exponential growth in your awesomeness – some more, some less, but I think most of us look at our period in college as being awesome, and we cruise on the increased awesomeness of that experience for a long time afterwards.

Of course, life doesn’t end at college. After a certain point, you have to acquire new skills, new perspectives. This can be clearly tied to your professional life or not – some things help us be more awesome in general because they make us happy, give us renewed energy, or just energize our brains. In order to go further, we need to pursue some new skill – maybe we take up windsurfing.

Woohoo!

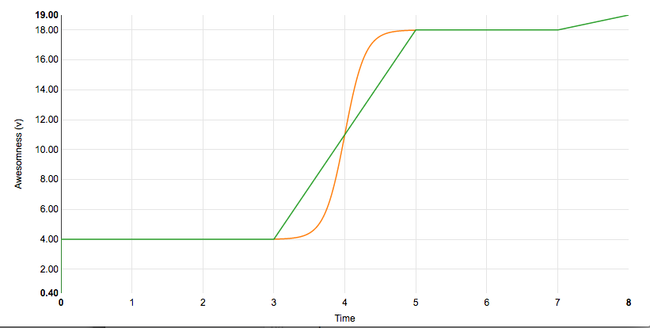

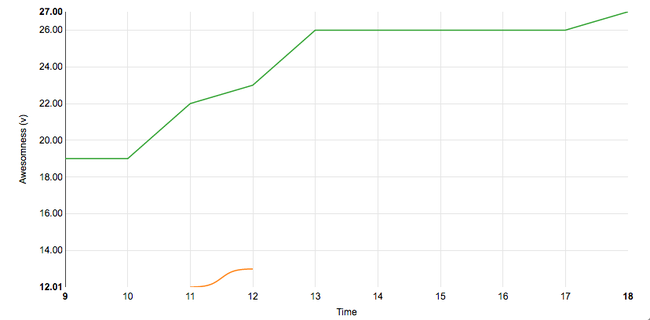

Of course, some S-curves are at a high level of entry: teaching calculus to a kindergartner? Looks like this:

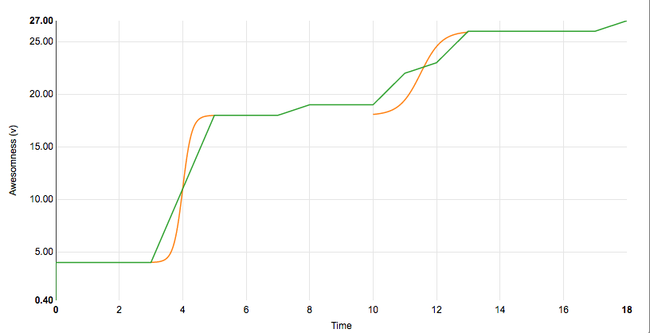

Not every pursuit provides a high return, especially as time goes on. Consider a highly successful businesswoman in the middle of her career1, and look at the improvement she would derive from exclusively focusing on her handwriting for a couple of weeks:

Not a lot, right? So this theoretical model seems pretty realistic to me2 and provides a fair explanation for several items that feel true:

- Progress comes in fits and starts

- The pursuit of certain skills, either via education or self-learning, provides more value than others objectively (learning French vs. learning how to peel a potato)

- Some pursuits provide more value to some than they do for others, and sometimes that’s simply a function of timing (calculus to a five year old vs. calculus to a high school student)

- All pursuits eventually provide diminishing returns.

This provides some workable advice, as well. Essentially, in order to maximize general awesomeness, you should be pursuing the fast-growth portion of the S-curve as much as possible, and when something hits the stage of diminishing returns, move on.3

So, to me, this works on an aggregate level as well. Let’s take the examples above and replace “college” with “adopting agile practices”, “windsurfing” with “providing coffee to employees”, “teaching calculus to a kindergartner” with “JVM threading classes for accountants”, and “handwriting” as “Microsoft PowerPoint classes for a management consulting company.”4

So, this S-curve model applies directly to the experience of the company I opened the blog article with – as an organization, they implemented some really cool technology, and they flew up the S-curve and had a lot of fun doing it! Everyone was excited, but when they peaked there, they didn’t realize that there wasn’t anything wrong. That’s the key insight here – that it’s normal to level out! That’s what S-curves look like.

Final Thesis #

If you want to keep growing as a company or as a person, you have to chase the next S-curve, no matter how high you got on the last one, it’s the rate of growth that determines your happiness, not how high you are.

-

Assuming that calligraphy isn’t a core skill for this person, of course. ↩

-

You may notice that the windsurfing example above doesn’t actually really work here – there’s no reason why going to college before or after windsurfing would matter, and the graph doesn’t really demonstrate this. It massively complicates things, but a simplistic way of thinking about it is that general awesomeness, as defined here, is an aggregate of various smaller awesomenesses, so improving your “physical skill” awesomeness by windsurfing and your “knowledge” by attending college both impact your general awesomeness, but otherwise don’t really interact with each other at all. I am way too lazy to draw all of those graphs. :-) ↩

-

Of course, I’m completely ignoring the whole idea of energy and restoring it here, purely to keep this ridiculously long blog post from getting even longer. Being on the exponential side of the s-curve is exciting, but it’s also exhausting, and sometimes you need to coast for a little bit to get ready to charge up the next one. ↩

-

As someone who has actually invested some time in improving my handwriting, I think this analogy is pretty apt – a management consultant WOULD probably learn something from the class, but it wouldn’t be earth-shattering, and it certainly wouldn’t change their life. ↩